An Effective Lesson Plan Successfully Delivered

Education can often feel like a balancing act between curriculum standards and student engagement.

While juggling learning standards, extracurricular commitments, and the mountain of administrative tasks that accompany any teaching post, Educators are left asking themselves,

How can I engage with my students?

How can I equip students with critical thinking skills?

How can I avoid killing my students’ love of learning?

Professionals in the education field know the delivery of a lesson is just as important as the lesson content – it’s the method that determines how much is retained, and how much is lost in translation.

While educational governing bodies hand down a framework of learning outcomes for Educators to achieve in a given timeframe, these frameworks are predominantly content-driven and operate as a list for Educators to tick off as they proceed through the teaching year. The checklist is there to ensure that each student receives equal access to information, with the goal of providing a level playing field.

However, Educators are left to decide how best to deliver this information to the students in their particular classroom – and there, as the bard would say, is the rub.

“While these approaches include what we want to teach, they don’t often contain how we’re going to teach it,” says Peter Brunn, author of The Lesson Planning Handbook: Essential Strategies That Inspire Student Thinking and Learning.1

One such method of lesson planning is widely known as Backward Design, in which Educators begin their plan from their unit objectives – what a student is expected to know by the end of a course – and work backwards from there, designing lessons, projects, and assessments designed to lead students toward that final goal. Backward Design is what moves lesson planning from a checklist to a strategic action plan.2

Failure to Plan is Planning to Fail

If you intend to take a long road trip from one end of the country to the other, and you wish to make several pit-stops along the way to rest, refuel, and visit particular tourist attractions, do you hop in the car one morning and work things out as you go? Perhaps, but failure to plan your route means you run the risk of missing out on one of your desired pit-stops.

You might drive past one of your stops because you failed to check the order they come on the map, or you might miss out on an opportunity to combine stops because of their proximity. You might even drive the long way round, instead of consulting a map for a more direct route.

Whatever your desired journey, a failure to plan ahead is dooming yourself to figuring things out as you go along – and that’s where the details fall through the cracks.

If you’ve ever found yourself wondering “what do I teach this week?” and consulting your unit framework for an item you can tick off your checklist in the next lesson, you too might be suffering from a failure to plan the trip.

Backward Design Explained2

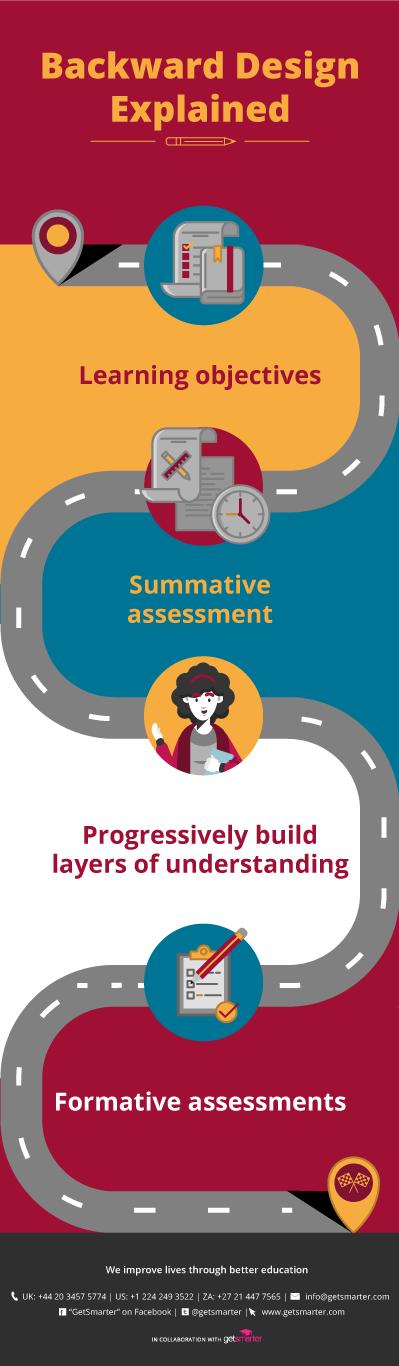

Backward Design is intended to help Educators to create lesson plans that focus on the goal, or bird’s eye view, instead of getting stuck in the process. While the exact application might vary with each setting or Educators, a basic roadmap can be followed:

1. Create an index of the learning objectives that students are expected to meet by the end of your unit, and a list of the essential knowledge, skills, and concepts that they need to support their understanding of the course content.

2. Design a summative assessment that students will complete at the end of the unit to prove their competency in the learning objectives. This could take the form of an exam, a writing assignment, a project – the format will be determined by the course material and your learning objectives.

3. Create a series of lessons, projects, discussions, and activities to help students progressively build layers of understanding and context, bringing them closer to the unit goals. Each lesson must have a specific objective – if you aren’t certain of the role your lesson plays in the greater scheme of your unit goals, how can you expect a student to see the value in the lesson content?

Resist the temptation to plan lessons that position you as the proverbial sage-on-the-stage. While it might seem easier to plan a speech and deliver it to a class of captive listeners, studies3 have shown that students respond best to an interactive inquiry-based approach which prompts students to examine their preconceptions and posits students as the author of their own learning process.

Presenting students with open-ended questions provides you with a way of encouraging their focused participation. A student’s ability to evaluate information, clearly articulate their thoughts, and debate effectively with others is a powerful tool to promote critical thinking and evaluate levels of understanding.

Judy Sheldon, field supervisor for student teaching at Syracuse University, advocates the need to create an environment that promotes higher-order thinking. “Find ways to let them reveal things, and put that into your plan. You might want them to interpret a map, analyze a document, and so on. Always make sure they are building their skills.”4

Provide students with a forum for reflection at the end of each lesson, where they can summarise what they’ve learned and help each other to close any gaps in knowledge.

Above all, make your lessons relevant and relatable. Students are not motivated to learn something because it’s on their exam – place things in context to help students understand the role this knowledge or skill can play in their own lives. Add context to your lessons by looking for ways to incorporate your students’ interests or cultures – if students can draw some personal links with the subject matter, they retain more knowledge.

4. Design a series of formative assessments to serve as checkpoints to determine students’ depth of understanding along the way.

At the end of a unit, it’s important to reflect and review the process you followed – what worked and what didn’t – and make adjustments as needed to improve delivery the next time around. Teaching, after all, isn’t only for students – effective Educators never stop learning themselves.