Greenwashing: How to spot and stop false sustainability claims at your organisation

Shoppers are putting their money where their values are, creating a powerful economic incentive for businesses to prioritise environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals.

64% of consumers believe that companies have a responsibility to solve climate and environmental issues.1 These commitments align with broader international efforts, such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which call for urgent action to create a more sustainable world.

Casting a company in a green light can be profitable: Products making ESG-related claims averaged 28% cumulative growth over a five-year period, compared to 20% for products without such claims, according to a 2023 McKinsey study.2

But what happens when sustainability claims are just for show?

Companies that try to reap the benefits of seeming sustainable without making actual change are greenwashing, or misleading consumers about environmental practices to benefit their public image.

When companies exploit consumers’ desire to make environmentally responsible choices, they challenge trust and undermine genuine sustainability efforts.

What is greenwashing?

Greenwashing, also known as green marketing or green sheen, is the act of communicating misleading or false claims to make a company appear more sustainable than they are in practice.3

For example, a company might tout that their clothing is “sustainably produced and shipped,” but still use synthetic fibers and non-recyclable packaging, among other unsustainable choices. In this case, there is a gap between symbolic gestures, like green logos or eco-labels, and substantive, day-to-day actions.

Companies achieve this misrepresentation through methods such as press releases about green projects or sustainability task forces, rebranding products or services, and advertising materials.

Dr. Victoria Hurth, fellow at the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, says greenwashing can be deliberate or come from a place of ignorance. “In either case the idea of being ‘green’ is washed out of its meaning for those receiving the message,” Hurth explained.

Examples of greenwashing

Volkswagen’s “Clean Diesel” engine

One greenwashing example is the Volkswagen “Clean Diesel” engine scandal. VW heavily marketed new low-emissions diesel technology as more environmentally friendly than other gasoline cars.

In reality, Volkswagen was fitting their vehicles with a “defeat device” that reduced emissions during emissions tests. On the road, their engines emitted nitrogen oxide pollutants up to 50 times the legal limit in the United States.4

This led to a host of regulatory fines and several false advertising lawsuits being filed against VW, which cost the company $35 billion and resulted in millions of vehicles being recalled.5 Five years after the scandal, the company’s stock was still valued at 35% below its previous levels.6

In 2025, ten years later, courts are still ruling Volkswagen liable for the defeat devices and convicting former employees of fraud.7, 8

“There is an incentive not to look beyond the surface of a green message – it can be like a silent agreement that buyer and seller have to enable actions they would otherwise feel bad about.”

Dr. Victoria Hurth, fellow at CISL

H&M conscious clothing

Clothing brand H&M faced criticism from European watchdog organisations over its “Conscious Choice” collection – marketed using environmental scorecards and claims that products were made with more sustainable materials.

A 2022 Quartz investigation found that among the scorecards claiming an item of clothing was better for the environment, more than half were no more sustainable than comparable items made by the company and its competitors.9

The data for the scorecards comes from an industry-metric called the Higg Index. In a notice to H&M, the Norwegian Consumer Authority labelled the data as misleading and a breach of Norway’s marketing laws.10

That same year, H&M made commitments to the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) to adjust or remove sustainability claims from their website “in order to minimise the risk of misleading practices involving sustainability claims.”11

How to spot greenwashing

It might feel easier for consumers to take sustainability claims at face value. As Hurth notes, “There is an incentive not to look beyond the surface of a green message – it can be like a silent agreement that buyer and seller have to enable actions they would otherwise feel bad about.”

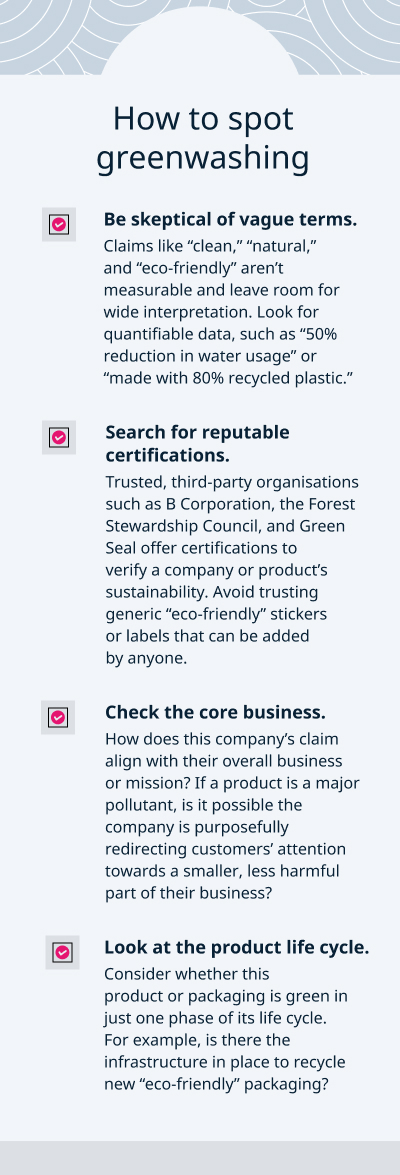

Exercising due diligence can help shoppers spot deception and make an informed choice. Consumers can look out for vague terms and explore the company’s mission and supply chain to find out more information. There are also certifications from trusted organisations that can help verify a company or product’s sustainability.12

Why should companies care about greenwashing?

As the demand for green practices increases, many companies might opt for the easy way out by using greenwashing to appear environmentally responsible. However, appearances will only get businesses so far. Governments, regulators, and stock markets are pushing forward mandatory disclosures on environmental impact.

When companies engage in greenwashing, the consequences extend beyond the PR department:

- Erodes trust: When consumers realise they’ve been misled, their trust in the company can decline. 54% of consumers say that they would stop buying from a company if they were found to have been misleading in their sustainability claims, according to KPMG research.13

- Legal and financial liabilities: When companies deceive consumers with false or misleading claims, they open themselves up to regulatory punishment. Fines for breaking consumer protection laws and even criminal sentencing for fraud are potential outcomes for companies.

- Undermines genuine ESG efforts: Without clear and substantiated claims, the validity of other sustainability efforts can also diminish in the eyes of consumers. For example, 76% of consumers express skepticism about “green” labels on products.14 False claims water down the validity of genuine ones.

How to avoid greenwashing at your company

2 out of 3 consumers doubt that companies are genuinely committed to sustainability.15 How can you help change that in your own organisation?

- Use clear, specific language. Use precise language when making environmental claims and set realistic goals for future progress.

- Act first, share later. Prioritise progress over marketing those ambitions to customers. When companies make progress towards meaningful ESG goals, the PR can be more specific, data-driven, and confident.

- Track goals publicly. Commit to keeping your customers updated on your progress over time. One example is Microsoft’s Environmental Sustainability Report — detailed transparency can boost trust in your organisation.16

“As executives and citizens, we all have a role to play in directing, overseeing and accounting for investment that works for the challenges we face in reality,” Hurth said.

Professionals of all levels – not only those in leadership positions – need to take on the challenge of driving meaningful, sustainable change. To achieve this, workers can upskill with online sustainability courses.

The Business Sustainability Management online short course from the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership is geared towards working professionals who want to strengthen corporate social responsibility efforts and implement sustainability in their organisation. Over eight weeks, you’ll learn to develop and motivate an action plan for sustainable business practices and consider corporate sustainability in your organisation – affecting real change, not just greenwashing.

Deepen your knowledge of organisational sustainability with an online course.

FAQs

What is greenwashing in simple terms?

Greenwashing is when companies, either intentionally or unintentionally, make misleading or false marketing claims about their sustainability efforts or the environmental impact of a product.

Is greenwashing illegal?

Greenwashing tends to fall under consumer protection laws around unfair or deceptive marketing, which vary by country. For example, in the U.K., the Competition and Markets Authority oversees the “Green Claims Code” — guidelines that help businesses meet legal obligations when making environmental claims.17 In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has a similar perspective, called “Green Guides.”18

What is an example of greenwashing?

One example of greenwashing is when companies advertise a product as “100% natural” or “made from eco-friendly materials” without providing specific details or evidence that support these claims.

Why is greenwashing bad?

When companies engage in greenwashing, they can damage their reputation and relationship with customers, experience legal and financial punishments for breaking consumer protection laws, and undermine genuine sustainability efforts around the world.

- 1 (2025). ‘Sustainability sector index 2025.’ Retrieved from Kantar.

- 2 (Feb, 2023). ‘Consumers care about sustainability — and back it up with their wallets.’ Retrieved from McKinsey & Company.

- 3 (Nd). ‘Greenwashing — the deceptive tactics behind environmental claims.’ Retrieved from the United Nations. Accessed on October 27, 2025.

- 4 Hotten, R. (Dec, 2015). ‘Volkswagen: The scandal explained.’ Retrieved from BBC.

- 5 Petrequin, S. (Dec, 2020). ‘Volkswagen loses top EU court case in diesel scandal.’ Retrieved from AP News.

- 6 Colvin, Geoff. (Oct, 2020). ‘5 years in, damages from the VW emissions cheating scandal are still rolling in.’ Retrieved from Fortune.

- 7 (Aug, 2025). ‘Volkswagen liable for defeat devices, top EU court rules.’ Retrieved from Reuters.

- 8 (May, 2025). ‘Four former Volkswagen managers convicted of fraud in ‘dieselgate’ trial.’ Retrieved from The Guardian.

- 9 Shendruk, A. (Jul, 2022). ‘Quartz investigation: H&M showed bogus environmental scores for its clothing.’ Retrieved from Quartz.

- 10 (Jun, 2022). ‘Potentially misleading environmental claims in marketing — using Higg MSI data in marketing of garments.’ Retrieved from the Norwegian Consumer Authority.

- 11 (Sep, 2022). ‘Going forward, Decathlon and H&M will provide better information about sustainability to consumers.’ Retrieved from the Authority for Consumers & Markets.

- 12 (Nd). ‘Standards and certifications.’ Retrieved from the U.S. Library of Congress. Accessed on October 29, 2025.

- 13 (Sep, 2023). ‘Over half of UK consumers prepared to boycott brands over misleading green claims.’ Retrieved from KPMG.

- 14 (2025). ‘Sustainability at the crossroads: Visualizing sustainability.’ Retrieved from Getty.

- 15 (2025). ‘Sustainability at the crossroads: Visualizing sustainability.’ Retrieved from Getty.

- 16 Smith, B. & Nakagawa, M. (May, 2025). ‘Our 2025 environmental sustainability report.’ Retrieved from Microsoft.

- 17 (Sep, 2021). ‘Green claims code: making environmental claims.’ Retrieved from the U.K. Competition and Markets Authority.

- 18 (Nd). ‘Environmentally friendly products: FTC’s Green Guides.’ Retrieved from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. Accessed on October 30, 2025.